To say The Drones have entered darker and weirder territory on their latest record, Feelin Kinda Free, is a foreboding statement. The band, officially now a five-piece, have been gleefully mutating into strange and brilliant musical anarchists since their 1997 inception.

But they’ve found a way.

In this candid conversation I discuss Feelin Kinda Free with The Drones’ wry and wicked mastermind, Gareth Liddiard. From extraterrestrials to the influence of the Wu-Tang Clan, we cover a range of subjects – each channelled through the songwriter’s unhinged door of perception.

How did the band’s approach to the writing of Feelin Kinda Free compare to I See Seaweed?

We just wanted to get away from the tropes. With the last record we recorded it sitting around in a circle, and we wrote it like that. Well, I wrote it and then we figured it out while sitting around in a circle. When you’re working like that, a lot of the shit you play is for expedience because you have to keep up with everyone else. That sounds like it would suck. Basically, the thing is you do what you do. I wanted to get away from that. I wanted everybody, rather than do it off the top of their heads, actually consider what they’re doing and maybe do something they wouldn’t do. It was really good. Just because you play guitar doesn’t mean you need to “play guitar”. It took a while but everyone got it in the end. Everyone did the “what wouldn’t I do” and then they did it. It’s pretty cool, and it still sounds like us.

That experimentation is evident. It’s quite a challenging listen.

You have to listen to it ten times, but that’s alright. There’s not many records like that anymore. Once upon a time my generation were trained to deal with that kind of stuff. With shit like Led Zeppelin or Sonic Youth or Jane’s Addiction. Everything now is fuckin’ retro, so it’s all been done – you already understand it. The minute you press play you know whether it’s going to sound like early ’70s Rod Stewart or the New York Dolls or Joy Division. You already get that. We’re not working on that. We’re working on what it was like to first hear Joy Division, where it’s “What the fuck is this?” You have to figure your way through it.

The only thing I’ve come to expect from a new Drones album is the unexpected, so you’ve certainly created that anticipation from album to album.

I See Seaweed kind of wrapped up it all up – that’s what we sounded like up until that point. We can do that. With something like the new album, if people go, “Oh my god, they’ve changed!”, then come to the live show. It’s not that different. In a weird way, we’ve always meant to do that, I’ve always meant to do this album, where it’s completely weird. When we first started we were so strangely weird that we couldn’t get a gig. We had to normalise to get in the door.

Last year you toured your classic album Wait Long By The River and the Bodies Of Your Enemies Will Float By. Did taking stock in that older material influence your decision to push the envelope even further this time?

Not really, we were 75 per cent of our way through the [new] album by the time we did that Wait Long thing. And we’ve been playing all that shit for years, so people sort of think “well, they’re having to go back and relearn or reconsider the old shit” but it’s like, man we’ve been playing that for fuckin’ 10 years. So it was one rehearsal then off to the Opera House. There wasn’t really much to it.

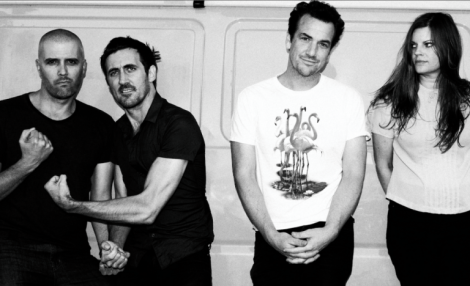

THE DRONES: Christian Strybosch, Gareth Liddiard, Dan Luscombe and Fiona Kitschin.

What was it like having drummer Christian Strybosch back in the band this time. Was there a sense of nostalgia?

Yeah, there was. It was quite trippy because the last time he was in the band was 2004. He went and got a life for 10 years and did everything he felt he needed to do. When we were doing music, it was all-encompassing. Although he’s a really natural musician and a very, very musical guy – he’s a musician, you know – he wanted to have a family and stuff like that. So he couldn’t come on tour with us and all that shit, those big long tours we were doing at the time, so he went and did everything that he needed to do, planted his wild oats and set down roots, and got that all done in 10 years. Got a career and shit.

It was funny, because Mike [Noga] left and Fi [Kitschin, bassist] just got on the phone – and we’ve been friends with him [Chris] for the entire decade he hasn’t been in the band. We hang out. He would often get a phone call from us. This time Fi rang him and said, “Hey, Chris, how are you?” and he’s like “Oh yeah, good,” and she’s like, “I want to ask you something…” and he went, “…yes?” He was really keen to get back in.

So there was that sense of nostalgia but it was also refreshing because he was so unjaded. The biggest crowd he would have played to in The Drones would have been something like 350 people at the Tote. Then his first show was like 3000 people, some shit like that. So he was really excited and that rubbed off on us.

How does Chris’ approach to the drums compare to Mike’s?

Chris would be more jazzy, or something… Mike would be more modern. Mike played in a band called Legends of Motorsport, which are like a really cool, sort of… they border on metal. Where as Chriso likes jazz, just crazy spaz-out old-school drums. But he was also really into programming drums and using samples and basically treating it more as a hip-hop guy would, or someone like Radiohead would, or Deerhoof or Missy Elliott – although he’s more traditional, in the jazz sense, he’s not traditional at all. So that was really cool, because a weird band has a weird drummer. If you have a normal drummer, you’re a normal band. And Mike was never keen to get off the acoustic kit. So we were like, “Man, we need to change the drums up because we need to change the band up” and was like, “Cool.” He already had an electronic drum kit, he was into it. He loves Joy Division, he loves Radiohead, he loves Missy Elliott. He likes hip-hop.

“There’s a bunch of websites where they rate it one of the top ten murder mysteries of all time and no one in Australia knows about it. If it had happened in America, we’d all know.” – Liddiard comments on the Taman Shud Case.

It’s funny you mention hip-hop because I listen to some of these songs and I hear that influence in how you spit the lyrics, and the patterns and rhythms. Has rap been an influence on you this time?

I wanted to not have ten-minute songs anymore, because we’d been there and done that. I guess to compress something down you have to edit shit down and that format, something like the Wu-Tang Clan, a word spew in three and a half minutes, it works. If you’re going to spit that much shit out you have to be rhythmical, and really groovy. Someone like GZA, or even someone like Ice Cube earlier on, good rappers are like good drummers, their tongue is like a snare drum. It’s amazing.

So, yeah, I went to that. We’ve all been listening to that shit since high school. Wu-Tang is twenty years old. We’ve been listening to Kate Tempest, who’s a chick from London, a hip-hopper, and, I don’t know… for some reason it just wound up hip-hop. We had a studio and the friend of ours who was in the studio too had a lot of hip-hop gear so we used that. And it’s a different way of writing. You can write on a guitar and that’s completely different to writing on a piano. Writing on a sampler is a different thing to that altogether.

Do you keep notebooks of lyrical ideas? Or do you write as required?

I start afresh, I do it all on a laptop and then at the end I delete whatever I didn’t use.

Anything that would forgive us and want to be our friend, even after knowing about the atrocities we’ve committed against our own kind, if aliens wanted to know us, that’s really fucking scary.

The record’s first single is ‘Taman Shud’, a devastating portrayal of the apathy of many Australians right now. Where did you get the idea to tie the song, thematically, to the ‘Taman Shud’ mystery of the body found on a South Australian beach in 1948?

Well, it’s a classic case of cultural cringe. It’s one of the most interesting unsolved murder mysteries of all time, it’s treated like that by boffins in the US and England – there’s an English band at the moment called Taman Shud. There’s a bunch of websites where they rate it one of the top ten murder mysteries of all time and no one in Australia knows about it. If it had happened in America, we’d all know. Everybody has heard of Ted Bundy and all sorts of weird shit, and conspiracies, but they’ve never heard of that. Because it’s Australian. People [Aussies] are just so disinterested in themselves and feel icky when they think about themselves. It’s there for that reason. This happened. This is weird. It’s really interesting. Everyone else knows about it. You don’t. And the verses are saying, while you’re there, think about this [too].

Has your approach to lyrics, in terms of imagery and metaphor, changed much over the years?

I guess I was learning along the way, so… yeah, sometimes you over shoot, sometimes you under shoot, it’s all the same thing. If you hit, that’s the only thing that matters. I guess I just sort of hit more now, that’s all. Sometimes you have to over shoot and under shoot just to know where the target it. It’s a learning process. I think I’ve found my equilibrium, otherwise there’s not much of a change.

I really love the new album’s final track, ‘Shut Down SETI’. There was a space reference on the previous record with ‘Leica’. Where did the idea of unfriendly aliens come from?

Last year, the last 18 months, SETI, which has been around for 30 years, maybe more, have decided to start broadcasting. For 30-odd years they’ve been listening and they haven’t heard anything, so they’ve thought maybe it’s time to broadcast. Even Hawking said an interesting thing, where he was arguing with the woman that runs SETI, he said, “Don’t fucking broadcast, you don’t know what you’re dealing with.” Even though it’s a long shot that there’s anything out there, he’s sort of saying what do you know about extraterrestrial life? Nothing. So there’s a 50-50 chance that this could be good or bad. If it’s bad, that’s really bad. [Hawking] says to her, “Do you think you’re good?” and she says, “Yeah.” And he goes, “Well, do you eat animals?” and she says, “Yeah,” and he goes, “Well, there you go.” (laughs) You might think you’re good, but animals don’t. Other living things don’t. He’s saying, you’re broadcasting out into that. There’s a 25 per cent chance that it will be okay. And, the thing is as well, for 30 years no one’s replied to us and you could say, “That’s because there’s no one there.” But there’s also the chance they are there but they’re not replying for a reason. Maybe they know, they’ve learned a lesson in the past about replying. There’s all sorts of reasons not to do this. It’s fucked up. If you did get in contact with something, it would know about us. If it came here it would know about the Holocaust, and it would know all the awful things. It would also know all the brilliant things we’ve done. Anything that would forgive us and want to be our friend, even after knowing about the atrocities we’ve committed against our own kind, if aliens wanted to know us, that’s really fucking scary. That is an amoral alien species and you don’t want to fuck with that.

But then it’s such a silly song. Why wrote a song about that and take it seriously? It’s like that ‘Oh My’ song. There’s a bit of mischief there because it’s such a stupid topic.

What’s next for The Drones after this Australian tour?

We’re going to do to the Australian tour and then we’re going to go to Europe, and then we’re going to come back. In the breaks we’ll be recording. I’ve got to start writing songs. So… yeah, just more of the same.